An efficient open-source automatic theorem prover for satisfiability modulo theories (SMT) problems.

View on GitHub

Downloads

Documentation

Tutorials

Blog

Join the Conversation

People

Publications

Awards

Third Party Applications

Acknowledgements

Newsletter

Partitioning Strategies for Distributed SMT Solving

by Amalee Wilson

Partitioning is a divide-and-conquer approach where a difficult problem is split into hopefully easier subproblems that can be solved in parallel. This strategy is notoriously difficult to get right with SMT problems. We found that while it’s no panacea, partitioning can be used to diversify solving and reliably improve performance in a portfolio.

Many users of SMT solvers find that the solver’s performance is the main bottleneck in their application, yet most SMT solvers remain single-threaded. We sought to explore a divide-and-conquer strategy for accelerating SMT solving. Six main strategies were explored, using three different sources of atoms for the partitions and two different types of partitioning. More details about these partitioning strategies and the various parameters can be found in the paper that we recently published at FMCAD 2023. Many of these partitioning strategies work well for the QF_LRA, QF_LIA, QF_IDL, QF_UF, and QF_RDL challenge benchmarks used for the paper (214 total). However, a central contribution was discovering that interesting new portfolio techniques could be applied using these different partitioning strategies. Portfolio solving is an approach in which multiple solvers (or different configurations of a solver), attempt to solve the same (or perturbed but equivalent) SMT problem in parallel.

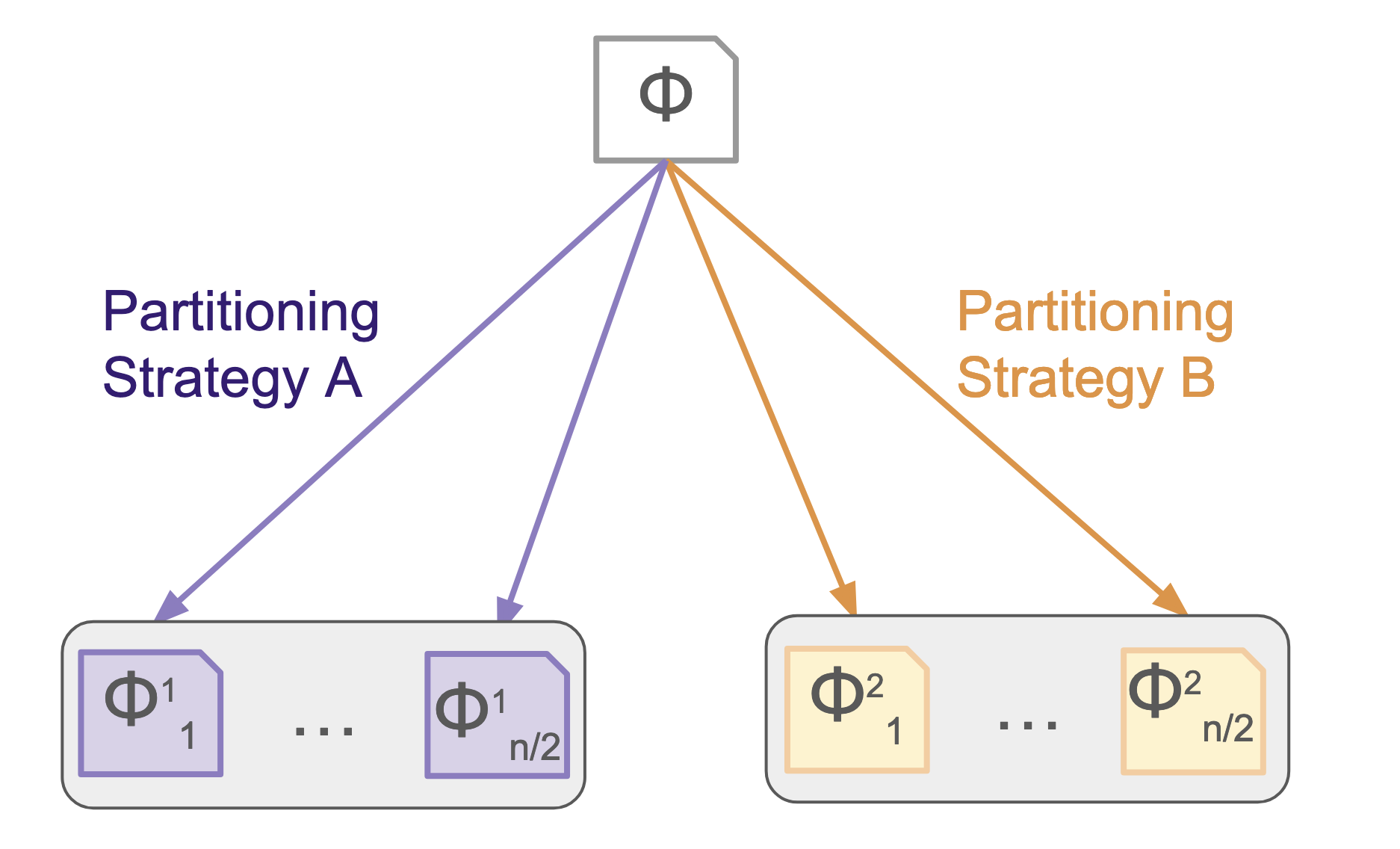

We noticed that different partitioning strategies worked well for different problems in the set of challenge benchmarks. There was no clear winner that reliably outperformed the others. So we chose to create a partitioning portfolio. The idea is that, for example, if there are 8 cores, then 2 different partitioning strategies can be used to create 2 sets of 4 partitions. Each of these sets of partitions can be solved in parallel, and when the first set of partitions is finished, the remaining 4 processes can be terminated. This approach is similar to a traditional portfolio solving strategy, but sets of partitions are treated as entries in the portfolio, as opposed to different configurations of the solver or permutations of the problem. Interestingly, the partitioning portfolio, with fewer partitions made by each strategy, can outperform a single strategy that creates more partitions at once. To be clear, two sets of 4 partitions run as a portfolio can outperform a single set of 8 partitions because one of the two sets of 4 partitions may finish before the single set of 8. This result was somewhat surprising because we expected that creating more partitions would almost always be better than creating fewer. However, the diversity introduced by using multiple partitioning strategies was more valuable than trying to further split the problem into more partitions.

|

|---|

| This partitioning portfolio has two sets of partitions. |

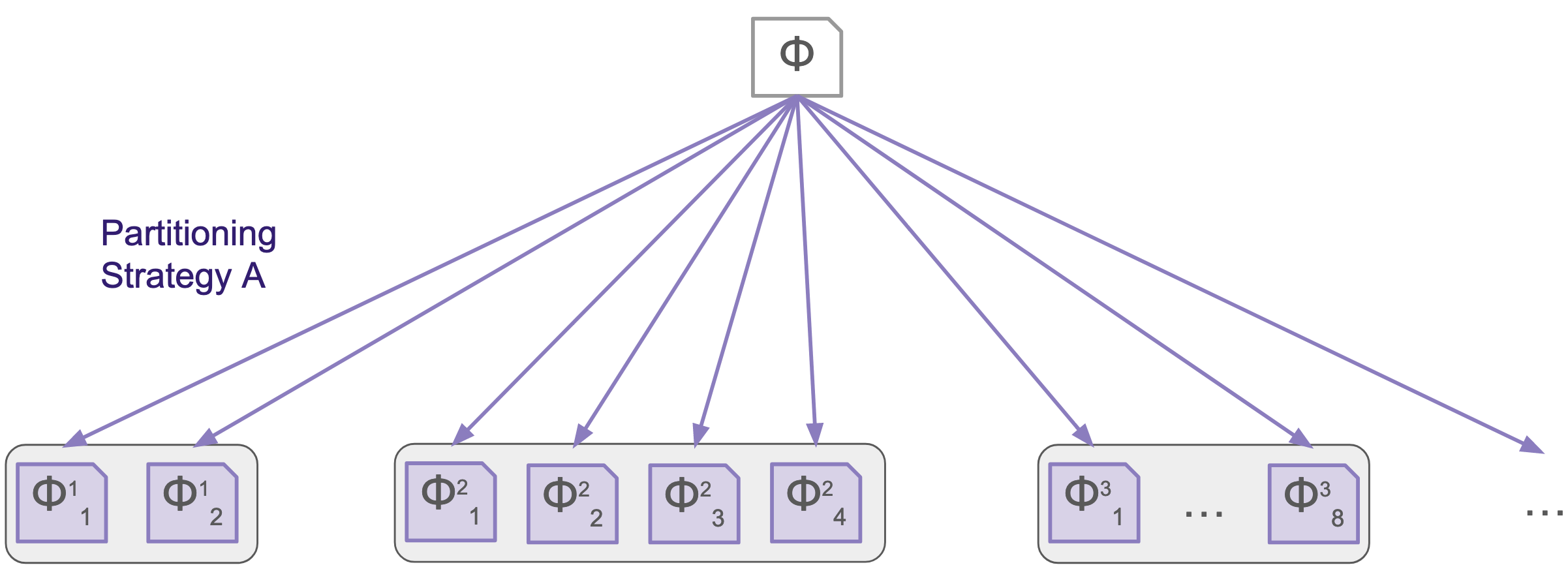

Even more surprising were the performance improvements that we observed using a graduated portfolio. This approach involves creating multiple sets of partitions from one strategy, and it can outperform a single set of partitions with the same resource limits. For example, a graduated portfolio of 2, 4, 8, and 16 partitions (for a total of 30) can outperform a single set of 32 partitions made with the same partitioning strategy. This observation is interesting because the diversity is not coming from using different partitioning strategies. Instead, simply varying the number of partitions made, even when the sets of partitions share literals, introduces sufficient diversity in solving to outperform a single set of partitions when the total number of available cores for solving is kept constant.

|

|---|

| The graduated portfolio introduces diversity by producing many sets of partitions with one strategy. |

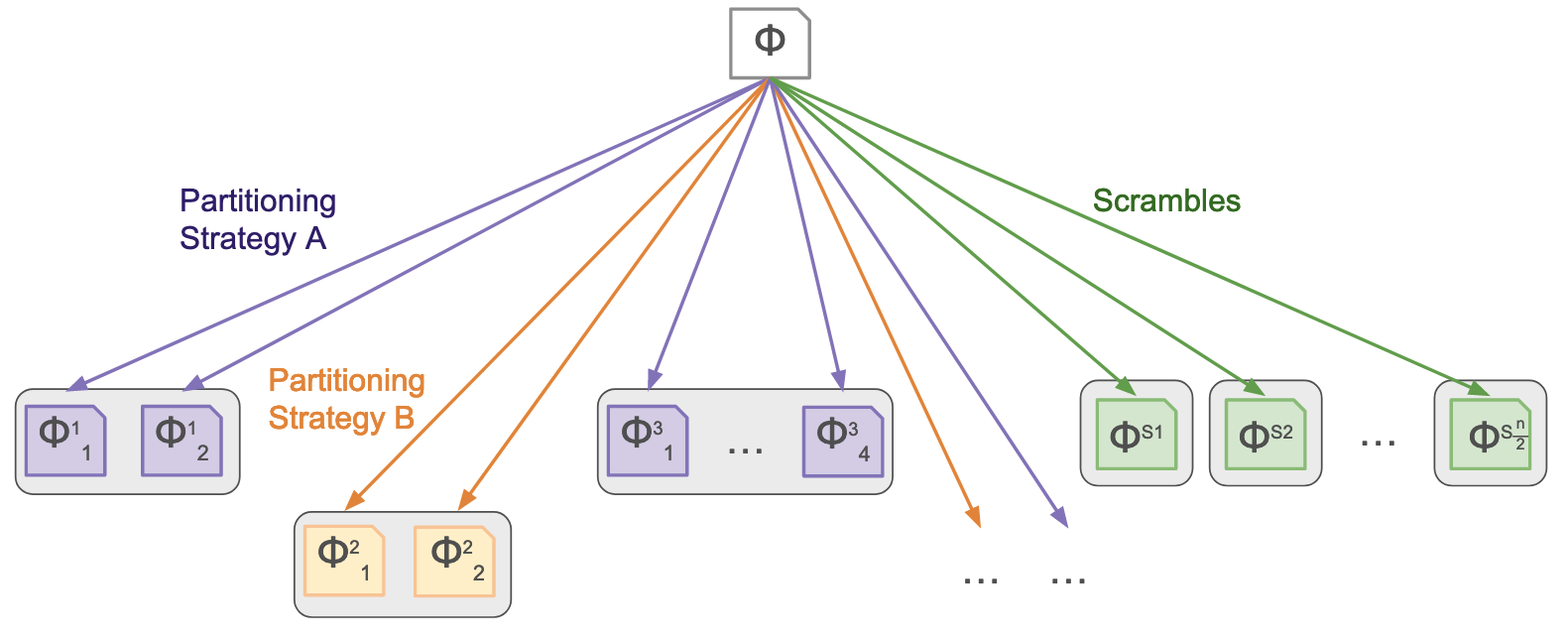

The best portfolio technique, though, is the hybrid graduated partitioning portfolio. We call this approach “hybrid” because it uses both the more traditional portfolio approach of scrambling (where semantically equivalent but mutated copies of the original problem are solved in parallel) in addition to using a graduated partitioning portfolio with multiple partitioning strategies. This interesting portfolio was motivated by the observation that each aspect introduces diversity into the portfolio: varying partitioning strategies, varying the number of partitions made, and introducing a non-partitioning-based strategy. Ultimately, we believe that scrambling introduces a different type of diversity into the portfolio, and we support this claim in the discussion of the final figure in the paper.

|

|---|

| The hybrid graduated portfolio uses half the cores to solve scrambles of the original problem and the other half to solve sets of partitions. |

If you’re interested in trying out some of our partitioning strategies, they can all be found in cvc5’s main branch on GitHub! Here’s how you use it:

For 8 time-based, cube-type partitions:

cvc5 --partition-when=tlimit --compute-partitions=8 --partition-start-time=3 --partition-strategy=decision-cube problem.smt2

--compute-partitions=8 communicates that 8 partitions should be made, and 8 can be replaced with the desired number of partitions (must be a power of 2 for cube type partitions).

--partition-start-time=3 communicates that the partitioner should wait 3 seconds before creating partitions, and although 3 can be replaced by any number of seconds, it is empirically a good choice.

--partition-strategy=decision-cube communicates that cubes should be made based on decisions. This parameter can be replaced in this code snippet with either lemma-cube or heap-cube.

Additional documentation for different partitioning parameters, including scatter partitions, can be found under the parallel options documentation. Note that this code snippet only produces the partitions — it does not solve them.

Edited on January 26, 2024: Based on questions that we have received about this blog post, we wanted to clarify the output of the partitioning.

- If no partitions are produced, and the output of cvc5 is

satorunsat, then cvc5 successfully solved the problem without partitioning. The output is the final answer. - If partitions are emitted followed by

unsat, this is expected behavior, even for a satisfiable problem. The partitions need to be solved to determine the final answer. - If partitions are emitted followed by

sat, this means that the problem was found to be satisfiable during partitioning. The partitions do not need to be solved in this case.

To solve the partitions, each of the partitions must be appended, separately, to the original problem, and these copies corresponding to each partition must be solved in parallel. cvc5 does not do this for you, but a straightforward Python or Bash script can achieve this task.

Amalee Wilson is a PhD student advised by Clark Barrett in the Stanford Center for Automated Reasoning (Centaur) Lab. Her PhD work is focused on strategies for distributed SMT solving.

Check out our GitHub Discussions if you have any questions.

Back to All Blog Posts